“At a big picture level there's a sense of disengagement and dissatisfaction in rural areas and a sense that their needs are not really considered in decision making.”—Natalie Egleton, CEO, Foundation for Rural & Regional Renewal

Key points

- Regional Australians are leading the way in personal relationship but falling behind when it comes to health, according to recent Australian Unity Wellbeing Index results.

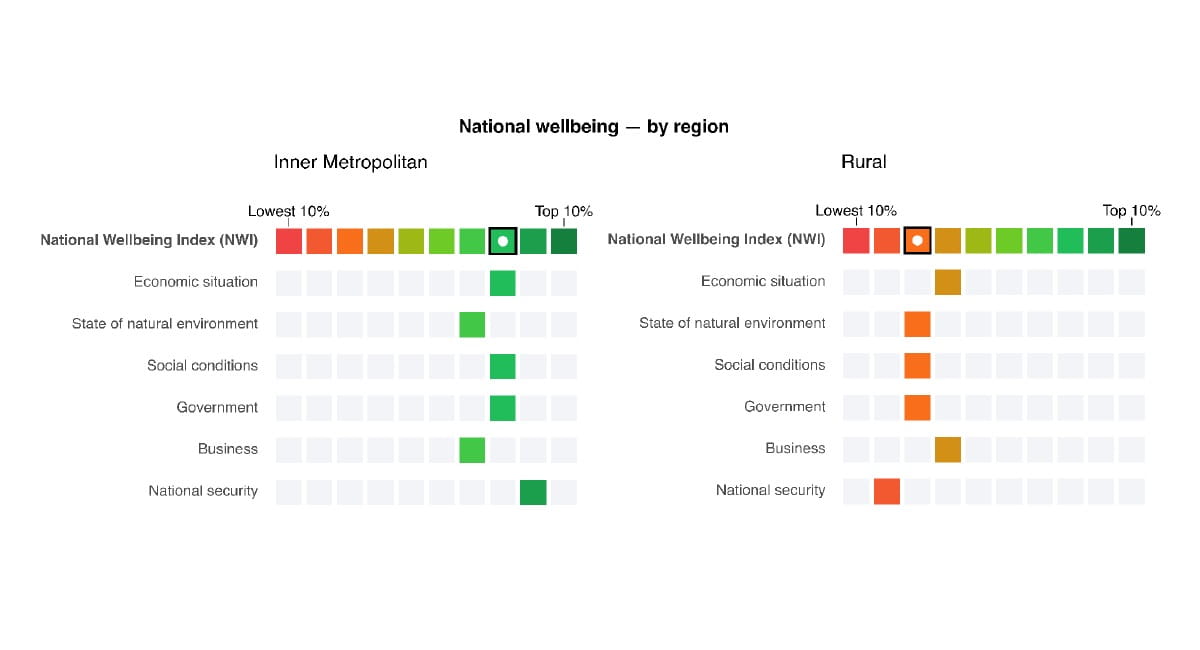

- Satisfaction with the state of the nation varies greatly across the country.

- Representation is needed for regional Australians to ensure their voices are not only heard but also upheld in policy making.

Who’s happier: those living in the city or the country? It’s an ongoing debate amongst Australians and unsurprisingly the answer isn’t a straightforward one.

Results from the latest Australian Unity Wellbeing Index (AUWI) survey, undertaken in partnership with Deakin University, offer some insights, but they also point to a national wellbeing gap.

This year’s AUWI mapped the personal and national wellbeing of Australians based on electorates. It categorised results based on the Australian Electoral Commission regional classifications (inner metro, outer metro, provincial and rural), which allowed us to paint a picture of how wellbeing shows up across the country.

“For personal wellbeing, when we collapse and average everything down across those four regions, they're actually quite similar,” says lead researcher, Dr Kate Lycett.

“But national wellbeing was a different beast. There were big differences across the different regions.”

You can see how your electorate rates its wellbeing in the AUWI Dashboard here.

Community connectedness in the country

While Personal Wellbeing Index scores were fairly similar across all four electorate regions, with rural areas reporting a slightly higher score, there were notable differences in certain areas of personal wellbeing.

Two categories in particular offered big location-based differences: health and personal relationships.

Inner metro electorates had the highest satisfaction with health, which Kate says may reflect more easily accessible health services in those areas. Personal relationships, however, were rated significantly lower in metro areas compared to rural electorates.

“Building social capital and community connectedness could help strengthen satisfaction with personal relationships in the metropolitan areas,” says Kate.

Rural electorates, on the other hand, reported the highest satisfaction with personal relationships and the lowest satisfaction with health.

Health services

Foundation for Rural & Regional Renewal CEO, Natalie Egleton, says that while some regional areas have leading healthcare models, it's the more remote areas where people are often facing layering of disadvantages when it comes to health services access.

She gives the example of some Australians needing to travel up to ten hours to get to the nearest major healthcare hub.

“There’s a whole stack of barriers to that,” she says.

“You need to have a car, you need to be able to afford the fuel, you need to ensure that the weather is okay to drive in, you need to leave your business or your farm ... There might be an age factor. There might be a carer factor, if you've got young children or you're caring for parents or other family members. So, you just end up with all of these stacked disadvantages.”

Natalie says the result is that a lot of people simply won’t go to the doctor for things that they should.

“And then, what you see is preventable health issues and preventable diseases becoming quite chronic in rural areas.”

The national wellbeing divide

So, how does national wellbeing play out across the country? Data shows the starkest divide comes when you compare the national wellbeing of inner metro electorates with rural areas.

Kate says these inner-city electorates also happen to contain some of the wealthiest suburbs.

“All of the electorates in the top 10% on national wellbeing have higher incomes than the median household income,” says Kate.

However, Kate suggests it’s not just money that’s at play, and that policy could be factoring into the lack of national satisfaction from rural electorates.

“It seems like a lot of the inner-city areas feel like they've been heard in government and their ways of life are not being as impacted by some of the policy decisions that are happening,” she says.

“But if you're in a regional or rural area, you might be thinking, ‘well, hang on, I'm paying taxes. Why aren't I seeing the benefits? Why aren’t I seeing the services or roads that I expect?’.”

Natalie Egleton agrees that regional communities aren’t feeling heard and that while they are often consulted, they feel as though there’s no follow through on their input.

“At a big picture level, there's a sense of disengagement and dissatisfaction in rural areas and a sense that their needs are not really considered in decision making,” she says.

“People roll into town and say, ‘we're going to do things differently, we want to hear what you have to say’, and then nothing happens differently.”

Issues regional Australians are facing

According to Natalie, there are a number of issues regional Australians are facing that could be contributing to their low satisfaction with the nation including workforce challenges, access to essential services, housing, and absence of childcare to name a few.

“When you try to unstitch those issues, they come back to housing as one of the key levers,” she says.

“People can’t get housing, so they can’t move there and they can’t work there. Then if housing becomes unaffordable, people already living there can’t afford to buy there or stay there, which means those communities are really struggling to attract workforce or keep workforce, so there’s a knock-on effect.”

Effect of climate change

Climate and natural disasters are another significant issue for regional Australians.

“Rural communities have been really affected by disasters, and they continue to be. The last decade has been pretty intense when we think about droughts, fire, floods and then cyclones thrown in there. And for the communities that are experiencing all that, often consecutively, they largely feel like they get left behind,” says Natalie.

“There’s attention on these communities for a while and then it all goes away and they’re still left trying to clean up, but then another one happens.”

As a result, Natalie says there’s a strong call for more investment in mitigation and preparedness and resilience, and that that needs to flow into communities at a more local level.

Kate agrees that climate change isn’t playing out across the country evenly.

“When you think about the rural and regional areas in Australia, as well as people living on the coast, these areas are often impacted by bushfires, floods, coastal erosion and natural disasters,” she says.

“People's livelihoods, their houses, their communities, their lives are at risk unless we deal with climate change, and that is most abruptly felt in rural and regional areas.”

Change for rural communities

When it comes to national wellbeing, what can be done to turn things around for regional Australians?

Natalie says that representation in parliament is very important.

“Having bipartisan support for rural issues would be really helpful, as well as having a really clear rural lens on policy making. We have to ask ‘how is this actually going to land and what do we need to think about to make sure that this has benefits for the community?’,” she says.

“We need to understand the differences in the context in rural areas as well, because programs and services just don't work the same way in smaller, more remote areas as they might do in a city.”

.jpg)

.jpeg)